Article: The origins of English

...starting with the origins of humans

Where does English come from?

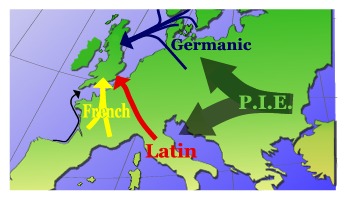

Modern English comes equally from Latin, French and Germanic languages. Most of the short everyday words in English are Germanic; most of the long technical ones come from French or Latin.

Modern English comes equally from Latin, French and Germanic languages. Most of the short everyday words in English are Germanic; most of the long technical ones come from French or Latin.

Click here for a table in which you can see the connections.

If you want to know where this Germanic-French-Latin mix comes from, you will need some European history.

Samples of English over 1400 years

Modern English has existed for about 400 years. Some of these examples are much older.

Old English, 650-950 AD (Beowulf, anonymous):

Old English, 650-950 AD (Beowulf, anonymous):

Hwæt! Wé Gárdena in géardagum þéodcyninga þrym gefrúnon·hú ðá æþelingas ellen fremedon.

Old English, or Anglo-Saxon, is a Germanic language.

I'm English, but I can't understand this.

Old English, 1100 AD (the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, anonymous)

Her Landfranc se þe wæs abbod an Kadum com to Ængla lande, se efter feawum dagum wearð arcebiscop on Kantwareberig.

I can understand a little of this.

Middle English, 1390 AD (Prologue to the Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer)

Middle English, 1390 AD (Prologue to the Canterbury Tales, Geoffrey Chaucer)

Whan that Aprille, with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote

And bathed every veyne in swich licour,

Of which vertu engendred is the flour

The first time I read this, I couldn't really understand it but I studied it at school when I was 13. "Whan" means when, "shoures" means showers, "soote" means sweet, "swich" means such, and "flour" is flower.

Late Middle English, about 1470 (Le Morte d'Arthur, Sir Thomas Malory)

King Uther sent for this duke, charging him to bring his wife with him, for she was called a fair lady, and a passing wise, and her name was called Igraine. So when the duke and his wife were come unto the king, by the means of great lords they were accorded both. The king liked and loved this lady well, and he made them great cheer out of measure, and desired to have had her love.

I can understand all of this easily. (The spelling in this extract has been modernised.)

Early modern English, 1595 (Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare - poetry)

Early modern English, 1595 (Romeo and Juliet, William Shakespeare - poetry)

Wilt thou be gone? it is not yet near day:

It was the nightingale, and not the lark,

That pierced the fearful hollow of thine ear;

Nightly she sings on yon pomegranate-tree:

Believe me, love, it was the nightingale.

I can easily understand this, but we no longer say "wilt", "thou", "thine" or "yon", we no longer use the subjunctive in the first line, and "fearful" has changed its meaning in 400 years.

Early modern English, 1666 (Pepys' Diary, William Pepys)

The Great Fire of London: ...all over the Thames, with one's face in the wind, you were almost burned with a shower of firedrops... When we could endure no more upon the water; we to a little ale-house on the Bankside, over against the 'Three Cranes', and there staid till it was dark almost, and saw the fire grow; and, as it grew darker, appeared more and more, and in corners and upon steeples, and between churches and houses, as far as we could see up the hill of the City, in a most horrid malicious bloody flame.

The Great Fire of London: ...all over the Thames, with one's face in the wind, you were almost burned with a shower of firedrops... When we could endure no more upon the water; we to a little ale-house on the Bankside, over against the 'Three Cranes', and there staid till it was dark almost, and saw the fire grow; and, as it grew darker, appeared more and more, and in corners and upon steeples, and between churches and houses, as far as we could see up the hill of the City, in a most horrid malicious bloody flame.

This is not exactly 21st century English, but it's easy to understand.

Most of the short, basic, English words like must and go are Germanic, from the same source as modern German, Swedish and Norwegian. The longer and more technical words are Latin or French.

Usually in English you have a choice of 3 words for each thing and each action. You use a short Germanic word (house or mouse) for normal conversation. For academic or business English, you use a longer one, and you can often choose between a longer word based on Latin or one from French (house = accommodation / residence, or mouse = rodent / murine). That's why the English language has more words than most other languages.

The English language and the British people are the result of many invasions from Europe. People have come here from Spain, France, Germany, Scandinavia and the Mediterranean. Even 2,000 years ago, people came from Italy and Africa to live and die in Britain. The written history of Britain started about 2,000 years ago but some of the language used in Britain is much older.

Prehistoric Europe

"Prehistoric" means "from the time before written records". Written records exist from Mesopotamia 5,000 years ago, but there was little or no writing in Britain until the Romans arrived.

Most things we know about prehistoric people in Europe are from their stone tools, and from bones - bones of humans, bones of animals. That's because stone is mineral (silica, aluminium, sometimes calcium) and the rigid part of a bone is also mineral (calcium phosphate). Bone generally lasts for thousands of years longer longer than cloth (textiles), leather or wood. Sometimes we find prehistoric stone, bone, shell, ceramic and metal tools and art. It is not surprising that we have found almost no prehistoric leather or cloth, and not much prehistoric wood. We have found prehistoric homes and burials; and monuments like Stonehenge. By comparing this "material culture" with other parts of the world, we can see how it spread. For example, we can see how a particular kind of stone axe or pottery spread across Africa, Asia and Europe. We can guess that some language went with it.

The Stone Age

We often use the expression "Stone Age" or "caveman" to mean "stupid", but our Stone Age ancestors were certainly not that. We know a lot about Stone Age cultures that existed recently. In North America they had agriculture, architecture, ceramics, leather, textiles, art, craft, politics and the archery bow. In Greenland they had the kayak, the umiak, the igloo, coastal maps, the dog sled and composite bows. In Australia they had religion, archives in song, the boomerang, the bullroarer, the didgeridoo and the woomera. In Oceania they had cloth, ceramics, huge statues, surfboards, astronavigation, ocean charts of waves and currents, and outrigger canoes that could take a community and its seeds and animals a thousand miles to a new island.

There are many things we don't know about the Stone Age in Europe, because it was so long ago that very few textile, leather, wood, clay, bone or even ceramic objects have survived. We think Stonehenge and the Pyramids are old, but they were made only 4,500 years ago. Compared to

the Old Stone Age (the Palaeolithic), that's nothing!

There are many things we don't know about the Stone Age in Europe, because it was so long ago that very few textile, leather, wood, clay, bone or even ceramic objects have survived. We think Stonehenge and the Pyramids are old, but they were made only 4,500 years ago. Compared to

the Old Stone Age (the Palaeolithic), that's nothing!

Picasso once said to Brassai, "What is preserved in the earth? Stone, bronze, ivory, bone, sometimes pottery, but only rarely objects made of wood, cloth or leather. This gives us completely incorrect ideas about early man. The most beautiful objects of the 'Stone' Age were certainly made of leather, of cloth and above all, of wood. Really we should call it the Wood Age."

We don't think these "cave men" spent much time in caves, except when the climate was really cold. We know that they had music and art. Probably they had the bow and arrow for hunting, but we don't know that. We know that the people of the Middle Stone Age (the Mesolithic) travelled to islands like Crete, Cyprus and Ireland, so they must have had good boats. We've never found one, but going to Crete means sea crossings of at least 40km. Archaeologists don't even know much about the lives of European people in the Middle Stone Age (the Mesolithic), the New Stone Age (the Neolithic) or the Bronze Age.

We think we know a little about the language of the European Stone Age.

1 million years ago

Archaeologists believe that all humans came originally from Africa.They have found stone axes in the same style ("Acheulean") from about this time in Kenya, Ethiopia, the south of Asia, the Middle East, Spain, France and Britain. The people who made them were not Homo sapiens sapiens like us. Tools of the same style were made by human ancestors like Homo ergaster and Homo erectus.

We don't know much about these people, because a million years is an incredibly long time. Although it was well after the dinosaurs, a million years was enough time for the Atlantic to get 20 km wider, for ice to come and go more than once across half the planet, and for land to rise out of the sea and disappear again many times. It is almost impossible for a bone or a wooden object to survive for such a long time. However, wooden spears made by these people have been found at Schöningen and at Clacton, next to bones from horse, deer and European bison. These ancient spears were excellently designed and made. In an experiment, modern athletes were able to throw replicas 70 metres. Not bad; until 1928, the Olympic record for throwing the javelin was less than 70 metres.

The Schöningen people were Homo heidelbergensis. Archaeologists believe that they used language like us, and that they lived in groups of about 20 people and hunted big animals. They had smaller brains than the average modern human.

250,000 years ago

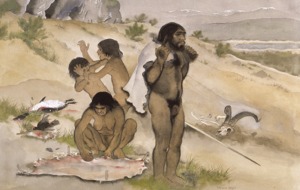

Neanderthal or Neandertal people (Homo sapiens neanderthalensis) were probably the descendants of Homo heidelbergensis, but they were much more like modern humans. If you saw a Neanderthal man in a city centre in Europe, wearing modern clothes, you might think he looked unusual, but not very unusual.

Neanderthal people were slightly shorter than the average European. They had thicker bones. The shape of the bones and the muscle attachments shows that they were a little heavier than us but much stronger. DNA testing indicates that they probably had pale skin, and that some of them had blue eyes and red hair. The brain of an adult Neanderthal was 10%-15% larger than the brain of the average adult human today.

Neanderthals were in Europe for five times longer than us, but we don't know much about them. For every thousand years that Neanderthal people lived there, only one individual left his or her bones to be found by modern archaeologists. And sometimes only one bone, or part of a bone, or just one tooth. It is likely that Neanderthal people often lived near the sea, where they could find not only animals, fruit and vegetables but also fish, shellfish and seaweed. Sea level goes down with every ice age, and up with every warm period. Europe was very cold for a lot of the time Neanderthals lived there, so many seaside homes, fireplaces, middens and tool-making places are now under 130 metres of water. Ordinary SCUBA equipment is safe only to 50 or 60 metres below the surface, so an archaeologist would need special diving equipment.

Neanderthal people arrived in Europe long before Homo sapiens sapiens existed. From a few archaeological finds, we know that they made tools from stone, bone and wood; they hunted large animals for meat, and they used fire to cook grains and vegetables. Click for a newspaper article about Neanderthal cooking. We believe they lived in small family groups of 5 to 15 people.

Neanderthal people arrived in Europe long before Homo sapiens sapiens existed. From a few archaeological finds, we know that they made tools from stone, bone and wood; they hunted large animals for meat, and they used fire to cook grains and vegetables. Click for a newspaper article about Neanderthal cooking. We believe they lived in small family groups of 5 to 15 people.

They sometimes lived in caves. In Ukraine, shelters have been found that were made by Neanderthal people from mammoth bones, but they probably lived most often in wooden shelters like recent hunter-gatherers.

We know they cared for the sick and buried the dead. At least, archaelogists have found several burials, and skeletons of Neanderthals who had a broken leg but lived long enough to recover from the fracture. You can't hunt, make a fire or even get water if you have a broken leg, so their family or tribe must have given them care and food until they could hunt again.

Until recently it was thought that Neanderthals were simple and stupid; half man, half ape. That's why the two pictures above show them naked. This tells us more about European scientists than it does about Neanderthals! It comes from the sort of racist anthropology that says early Homo sapiens sapiens didn't know that sex makes babies; or were too stupid to make boats, but were able to swim for 20-40 hours, in a straight line, towards an island 40 km away that is invisible from the water. Racist anthropology has also been used in attempts to justify slavery and genocide.

Neanderthal people lived in Europe during several Ice Ages, and they must have made good warm clothes. We don't know if they made cloth, but 100,000 years ago Neanderthal people at Neumark-Nord near Leipzig in Germany made leather using stone knives, bone tools (lissoirs) and liquid from the bark of the oak tree (tannin). Probably they also made leather using animal brains instead of tannin. Maybe they had good shoes and boots; we don't know.

Neanderthal people across Europe also made jewellery from stone, bone, shells and feathers.

We know they made red and black pigment from minerals. Red ochre is iron oxide or haematite. Like early modern humans, Neanderthal people put red ochre in graves when they buried their dead. They used a lot of red ochre, often carrying it long distances to their homes from the places where they found it, but we don't know what else they did with it. We do know what other people did, from the ancient Egyptians to 20th century Europe, and we know what Himba tribespeople in Namibia do with red ochre today. You can use it on its own, or mixed with fat or oil, for all sorts of things. Body painting, hair colouring or lip gloss; to prevent sunburn; as an insect repellent; as a deodorant; as a red paint to decorate walls, boats and weapons; as part of technique for preserving animal skins; and it helps with preserving food.

Neanderthal people did not have the same culture everywhere across Europe. Some still made tools in the old Acheulean style; some used adhesive to fix stone points to wood spears. In Syria and Romania they heated bitumen and asphalt to use as adhesives. At Campitello in Italy they made pitch from birch resin. It is difficult to make pitch. The process is called "dry distillation". You need the correct resin, you need a fire, and you need an airtight pot to exclude oxygen. The same technology has also been found at Königsaue in Germany, but that has been dated to a much later period and could have been either Neanderthal people or early modern humans. Click for an article.

It is likely that Neanderthal people were sailors too. Acheulean stone tools have recently been found in Crete, and scientists believe they are at least 130,000 years old. Crete has been an island since long before the time of Neanderthal people. To get there from the mainland means several sea crossings of about 50 kilometres, either via Rhodes and Karpathos, or via Cythera and Antikythera. Click here for an article, or see Stone Age Sailors: Paleolithic Seafaring in the Mediterranean by Professor Alan H Simmons.

It is possible that Neanderthalers made cave paintings using durable mineral pigments like later people. Read more here from Nature. However, if they did not make cave paintings with mineral pigments, it does not mean they were less creative than later people. They may have made cave paintings with organic pigments, or they may have preferred other forms of art made from wood or bone. Or maybe they just thought art was not very important. In 21st century Europe, we are happy to destroy forests and rivers, and let hundreds of species of animal become extinct, but we protect the Mona Lisa, which is just a small piece of canvas and paint. Maybe Neanderthals would think we are the crazy ones.

A digression: Are we more intelligent than Neanderthals?

Neanderthal people and the first Homo sapiens sapiens both had significantly larger brains than us - even after adjusting for the fact that bigger bodies have bigger brains. Unless there's something we don't know, that means they were both more intelligent than us. Most scientists assume that the Neanderthals were stupid because they didn't make big changes to their environment (farming, metals, cities, plastics). However, there are many possible reasons why we have changed the world more in 50,000 years than Neanderthals did in 250,000 years. For example, it could be that our brains are more efficient, cubic centimetre for cubic centimetre; but it could also be that Neanderthal people had different values to us.

One reason why many scientists believe that Neanderthal people were less intelligent than us is that they changed physically to adapt to cold during Ice Ages. Modern humans who live in very cold climates show some of these changes (short limbs, short necks, thick bodies), but not as much, because they have good clothing and shelters. Modern human values mean that we spend more than 90% of our time indoors, and we now spend nearly half the day looking at a computer, smartphone or TV. It is possible that Neanderthal people felt it was better to experience the cold, to confront it. To live a real life, not a virtual one.

Our culture today is the global consumer society, and its main value is "Always Get More". Donald Trump is the perfect example. Although he's a multi-billionaire, he still wants more. We think of it as the only possible way to live, but in the past there were many other Homo sapiens sapiens cultures. They had different values; not all of them wanted to have 135 pairs of shoes, gold-plated bath taps, servants and three houses; not all of them wanted to change the world. When I was at school, I was taught that our culture was the end of a process that started with farming, made the industrial revolution possible, and ended in "high mass consumption" with lots of cars and holidays, and that this was a good thing. Recently people have started to question this, partly because of sustainability, and partly because a consumer culture may not be as much fun as we think it is.

We live in a complex world of technology and systems, laws and social rules, taxes and benefits, insurance and pensions, contracts and subscriptions, stress and overwork, anxiety and depression, expectations and disappointment, resentment and suspicion, bullying and anger, loneliness and divorce, crime, prejudice, Facebook, alcohol, drugs, burnout, religious fundamentalism, New Age beliefs, data flood, instability, and change that gets faster all the time. We work longer hours than most other large mammals, and the mental health organisation "Mind" says that every year, 1 person in 4 has a mental health problem. For people who go out to work, it's 1 person in 3. As for sustainablity, the two problems are environmental change, and the fact that our culture and our multi-billion population now depend on oil, which will soon end. It may be necessary to change the "Always Get More" value after only 200 years of consumer society.

If Neanderthals had different values to us, it doesn't mean they were stupid. If you gave a Neanderthal person a choice between working in an office and having a pension, or living the life of the Plains Indians of North America, it is possible they would have chosen the Indian way of life. The Plains Indians were the tallest people on Earth when Europeans met them; historical anthropometry uses height as an indicator of good health and a good standard of living.

Neanderthal people didn't have farming, but they didn't need it. Their world had a lot more animals, birds and fish. (And, by the way, farming may not be so wonderful. The start of farming by humans was also the start of war - see below. And we were talking about historical anthropometry; humans got a lot shorter after farming was introduced. Farming means living your whole life in one small place. Subsistence farming means doing heavy, repetitive work all day. It means no holidays. And it's very unhygienic. Every year, your farm had more dirt and rats. Maybe farming wasn't such a good idea after all!)

Neanderthal people didn't have ceramic pots for cooking, but they didn't need them. It's possible to prepare hot food (including boiled, baked or grilled meat and vegetables, and even soup) using a cooking pot made of unfired clay, wood or even leather. Yes, it works; you can boil water in a leather bag over a fire. Or you can boil water by heating rocks in a fire and dropping them into water in a clay or wood bowl. In fact, if you have fire, a few rocks and some vegetation, you don’t even need the water. Try a Maori “hangi” or a New England “clam bake”. Incidentally, we have found ceramic sculpture by early modern humans that is 26,000 years old. Apparently it took us another 10,000 years (Japan) or 16,000 years (Europe) until we had the idea of making ceramic pots for cooking food!

Neanderthal people are often considered to be a separate species from modern humans. However, genetic researchers say that our people and Neanderthal people sometimes had children together. About 2% of human DNA today in Europe and Asia is from the Neanderthals. Read more here from the Smithsonian.

45,000 years ago

At about this time our own ancestors, Homo sapiens sapiens, arrived in Europe. We call them "European Early Modern Humans" or EEMH. They are also sometimes called the Cro Magnon people because the first skeletons were found in France, in a shallow cave or rock shelter called Cro-Magnon, or Cròs-Manhon in the Occitan language. It just means "Mr Magnon's hollow".Cro Magnon humans were the same sub-species as us, but a little shorter, stronger and probably a lot more intelligent than the average human today. Like Neanderthals, they had larger brains than us. It has been said that if their cave-painting artists were alive today, they'd probably be working for NASA. A big brain uses a lot of resources; even today, our brains use 20% of the calories and oxygen we consume. Most scientists prefer to ignore the fact that our brains have got smaller over the last 45,000 years, but there are a few theories. One is that the smaller brain size doesn't mean less intelligence, it means more efficiency, or less aggression, or both. Professor David C. Geary's theory is that we are less intelligent than our big-brained ancestors, and it's because we don't need to be as intelligent today. We now live in a protective society where people will survive and have children even if they're not very intelligent, so a big brain is less necessary. Click here for an article about this. Domesticated animals also have smaller brains than their wild ancestors.

Early Modern Humans lived in larger groups than Neanderthal people, but they started with a similar technology. They didn't go straight from zero to cities and ceramics.

Neanderthals had survived many ice ages, hunting large and dangerous animals like mammoths. They had already been on the planet for much longer than we have been, but they all died after we arrived in Europe.

So did the mammoth, cave bear, cave lion, panther, cave hyena, woolly rhinoceros, Irish elk, Cretan otter, pygmy elephant, pygmy hippopotamus, and later on the aurochs, tarpan, Portuguese ibex, Pyrenean ibex, and more recently nearly all European bison, beaver, wolves, bear, wild cats, lynx, great auk, sturgeon, monk seal, sea turtles and many other smaller animals, birds and plants.

So did the mammoth, cave bear, cave lion, panther, cave hyena, woolly rhinoceros, Irish elk, Cretan otter, pygmy elephant, pygmy hippopotamus, and later on the aurochs, tarpan, Portuguese ibex, Pyrenean ibex, and more recently nearly all European bison, beaver, wolves, bear, wild cats, lynx, great auk, sturgeon, monk seal, sea turtles and many other smaller animals, birds and plants.

In fact, every time Homo sapiens sapiens has arrived on a new continent or island, a lot of other species have disappeared. We can see this in the archaeological record, and we have many examples of both animal extinction and human genocide by Europeans. We're extremely aggressive.

Scientists say that the disappearance of Neanderthals is a mystery. Perhaps not a very big mystery, after all.

40,000 - 25,000 years ago

Planet Earth was cooler than today. Africa was hot, but northern Europe, northern Russia, Canada and some of today's USA were covered in permanent ice. Southern Europe was dry and sunny, but cold.

Neanderthal and Cro Magnon humans lived in Europe at the same time for 5,000 years, or perhaps as long as 10,000 years.

Neanderthal and Cro Magnon humans lived in Europe at the same time for 5,000 years, or perhaps as long as 10,000 years.

They shared the land with mammoths, woolly rhinos, aurochs, cave bears, horses, reindeer, bison and ibex, eagles and vultures. There were lots of predators, including giant cave lions, foxes and wolves.

By 43,000 years ago, Cro Magnon people were making music with bone flutes and no doubt also with drums, song, clapping and whistling. Some had domestic dogs.

They liked to cook their food, and there are indications that they made bread.

They liked to cook their food, and there are indications that they made bread.

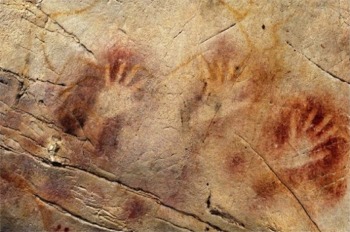

41,000 years ago at El Castillo in Spain, somebody, Neanderthal or Cro Magnon, made these hand prints with red and black pigment.

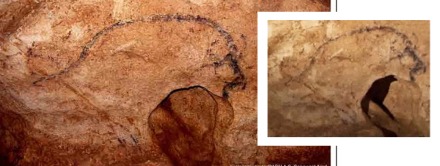

About five thousand years later, an artist in Coliboia, Romania, drew black outlines of eight animals. These are simple shapes. The bison is the best of them, because it uses the shape of the rock to create a three-dimensional (3D) effect with shadows.

About five thousand years later, an artist in Coliboia, Romania, drew black outlines of eight animals. These are simple shapes. The bison is the best of them, because it uses the shape of the rock to create a three-dimensional (3D) effect with shadows.

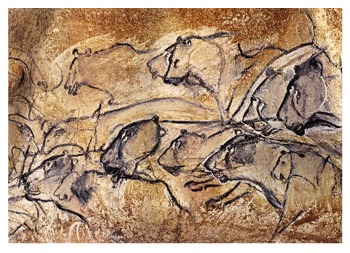

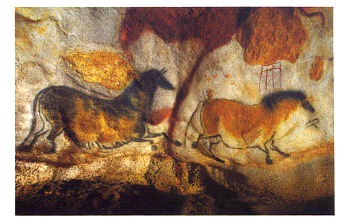

About five thousand years after that (about 30,000 years ago) Cro Magnon artists produced these superb, highly competent paintings of cave lions at Chauvet cave in France.

About five thousand years after that (about 30,000 years ago) Cro Magnon artists produced these superb, highly competent paintings of cave lions at Chauvet cave in France.

At Chauvet there are equally excellent paintings of horses, deer, rhinoceros and other animals.

At this time, cave artists painted only animals. They made very few images of people, and those are stylised like portraits by Picasso. Because of this, we don't know much about their clothing, or about activities like hunting, fighting and dance. For example, we don't know if they used bows and arrows to hunt.

Hunters at Sibudu Cave and Pinnacle Point in South Africa used the bow and arrow 71,000 years ago, probably long before our people left Africa. It is a mystery of archaeology that there is no sign of bows and arrows in Europe until only 7,000 years ago.

Hunters at Sibudu Cave and Pinnacle Point in South Africa used the bow and arrow 71,000 years ago, probably long before our people left Africa. It is a mystery of archaeology that there is no sign of bows and arrows in Europe until only 7,000 years ago.

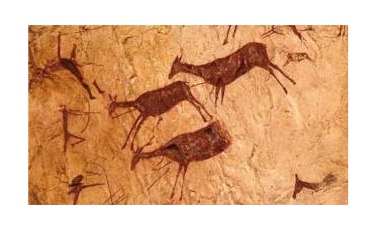

The oldest cave pictures of bows and arrows we have found in Europe are from 7,000 years ago in the Cova dels Cavalls (left) which is in the Barranco de la Valltorta in Castellón, Spain.

The earliest bows we have found are from about the same time, at La Draga near Girona in Spain and at Holmegårds Mose in Denmark. 7,000 years ago is not very long ago. It's only a few thousand years before the first major civilisations.

Let's return to the Palaeolithic, to the Europe of 25-40,000 years ago. Cave painters used symbols which probably had different meanings. If so, this was an early form of writing. 26 symbols have been found that are repeated in many painted caves in different parts of Europe over a period of 20,000 years. Click here for a newspaper article. Some of these symbols have also been found on later Stone Age jewellery like the necklace of the "dame de St-Germain-la-Rivière" from 15,600 years ago.

Cro Magnon people made sculpture of great power like the Lion Man of Hohlenstein (40,000 years old, see picture).

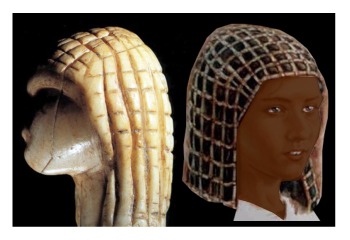

15,000 years later, another artist made the Venus of Brassempouy (picture below). The Venus on the left is the original sculpture; the Venus on the right is part of a graphic by Libor Balák. With apologies to Mr Balák, I have tinted it to show her as a black woman, which is more likely. Is the Venus wearing a cloth cap? It's possible. Archaeologists have found signs of cloth from 26,000 years ago at Dolni Věstonice in the Czech Republic; and traces of cloth dyed grey, black, turquoise and pink at Dzudzuana in Georgia - from about 33,000 years ago. It is possible that the Venus wore colourful and stylish clothing.

NOTE about skin colour: The ancestors of all humans lived on the open plains of Africa and were black people. In Europe 33,000 years ago, probably everybody still looked African, with dark brown skin, dark brown eyes and frizzy black hair. Dark skin is a protection against sunlight. If you live in a cold climate with less sun, you don't need much protection; in fact, it may be difficult to get enough sunlight for the body to avoid rickets, which is a disease caused by lack of Vitamin D.

NOTE about skin colour: The ancestors of all humans lived on the open plains of Africa and were black people. In Europe 33,000 years ago, probably everybody still looked African, with dark brown skin, dark brown eyes and frizzy black hair. Dark skin is a protection against sunlight. If you live in a cold climate with less sun, you don't need much protection; in fact, it may be difficult to get enough sunlight for the body to avoid rickets, which is a disease caused by lack of Vitamin D.

The first Europeans with light brown skin and brown eyes were born 30-40,000 years ago. This was partly the result of evolution to fit a new climate and partly (according to scientists at Harvard Medical School) the result of sex between dark-skinned Homo sapiens sapiens and light-skinned Neanderthalers. ("The genomic landscape of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans" Nature (2014) doi:10.1038/nature12961) The first modern humans with pale skin and blue eyes were probably born 6,000 - 10,000 years ago, when early Europeans started farming instead of hunting. Hunters get Vitamin D by eating a lot of meat. Farmers get less Vitamin D from their food, but if they have pale skin they can make Vitamin D from sunshine. Pale skin is an important mutation for a northern climate. Blue eyes were just an interesting genetic accident.

At this time, 30,000 years ago, the south of Europe had a nice climate but southern Britain was tundra like Siberia. England had long snowy winters, a lot of grassland and only a few small trees. We know from archaeology that there were a few people in Britain at this time. In 1823 the skeleton of one of them was found in a cave in south Wales.

The skeleton was wrongly named "The Red Lady of Paviland" but we now know it was a man aged about 25, who ate a good diet including meat, fish and shellfish. After he died, he was buried by his people and covered in red ochre that came from a location 20 km to the east.

The skeleton was wrongly named "The Red Lady of Paviland" but we now know it was a man aged about 25, who ate a good diet including meat, fish and shellfish. After he died, he was buried by his people and covered in red ochre that came from a location 20 km to the east.

The family or tribe of the "Red Lady" also left him jewellery made of mammoth ivory and sea shells. This is one of the oldest ceremonial burials ever found. At the time, the climate was colder, with more ice at the Poles, and sea level was 75 metres lower than today.

The cave is by the sea now, but when the "Red Lady" was buried, the sea was more than 100 km away and the cave had an excellent view over a wide, flat plain of grass. It was very useful for a family group of hunters.

However the climate was cold and getting colder; a time was coming when Britain would again be too cold for humans or even for trees. Britain was again an empty land for about 12,000 years.

18,000 years ago

Most of planet Earth was too cold for comfort. In Europe, there was an ice-cap 3 kilometres thick on the Alps. Humans still lived in southern Europe, in the warmer parts of France, Italy and Spain. Lots of ice on the land meant that there was less water in the oceans, so sea level was up to 130 metres lower than it is today. You could have gone from France to England to Ireland on foot, but the British Isles were covered in ice and snow.

Lots of ice on the land meant that there was less water in the oceans, so sea level was up to 130 metres lower than it is today. You could have gone from France to England to Ireland on foot, but the British Isles were covered in ice and snow.

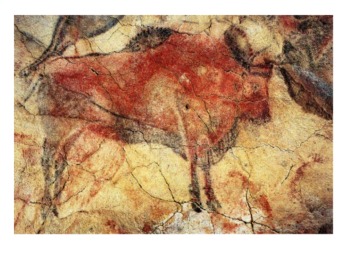

In the warmer south of Europe, people had time to make superb cave paintings at Lascaux in France 17,000 years ago (above) and Altamira in Spain (below). Painters probably visited Altamira at different times for 20,000 years.

15,600 years ago in the Dordogne, a young woman known as the "dame de St-Germain-la-Rivière" was buried with a necklace made from teeth of the red deer. At that time red deer did not live so far north. Their teeth must have come from several hundred kilometres further south. Sea shells, obsidian and jewellery were carried all over southern Europe, perhaps by exchange between different groups of humans. The family of this young woman also covered her body with red ochre.

15,600 years ago in the Dordogne, a young woman known as the "dame de St-Germain-la-Rivière" was buried with a necklace made from teeth of the red deer. At that time red deer did not live so far north. Their teeth must have come from several hundred kilometres further south. Sea shells, obsidian and jewellery were carried all over southern Europe, perhaps by exchange between different groups of humans. The family of this young woman also covered her body with red ochre.

NOTE about red ochre for burials: The custom we see in the Dordogne 15,600 years ago was the same at Paviland 30,000 years ago, at Skhul cave near Haifa 100,000 years before that, and perhaps even earlier in the Border Cave in the Lebombo mountains of southern Africa. There are indications that Neanderthal people in Europe had the same custom 250,000 years ago. Certainly they used red ochre for burials later on.

A thousand years after the death of the St Germain lady, the climate started to warm up fast. At one point 14,700 years ago, the temperature of Planet Earth increased by 6 or 7°C in only three years. The planet suddenly became a different place.

14,500 years ago

People began to come back to England. Scotland and Wales were still covered in ice and snow, and even England had long cold winters and short cool summers. 13,000 years ago, groups of hunters made camp-fires in caves around Cheddar Gorge in the west of England, and they left stone and bone tools, skeletons and possibly a simple rock carving of a mammoth. People probably lived in family groups. They didn't have enough food to live all year in one place, so they were nomadic. They often followed groups of wild horses for food.If it seems incredible that humans arrived in Britain at a time when the climate was so cold, it is even more incredible that they entered North America at about the same time. Scientists think they went across the Bering Strait. If Britain was tundra, just imagine how cold it was in Siberia and Alaska. From this time, there were modern humans on every continent except Antarctica.

12,800 years ago

Although Planet Earth was getting warmer, in just two or three years northern Europe suddenly became a freezer again. We know that at about this time humans lived in caves and ate each other, including men, women and children. The rest either walked south or died. The problem was that when the thick ice-cap over North America melted, a lot of very cold water entered the north Atlantic. It diverted the Gulf Stream, and northern Europe was again a place of constant snow and ice. This cold period is called the "Younger Dryas" or the "Big Freeze".11,500 years ago

The Gulf Stream returned, northern Europe started to warm up again, and our ancestors came back. Although the climate was still cool, things weren't all bad for the human explorers. There were huge numbers of fish, seals and shellfish in the cold and highly oxygenated water of the North Atlantic. Today fish are killed when very young by our industrial fishing techniques. The more our fishing technology improves, the fewer fish we catch and the further the boats have to go. In the Stone Age, individual fish lived a natural life which was much longer. As a result, the average fish was much bigger and heavier. One good fish would feed a family, and there were a lot more fish. Large animals including mammoths lived on the tundra, although the mammoths soon disappeared after modern humans came back.8,000 years ago

Time went by, and the climate got warmer. Summers in England were short but sometimes quite hot and sunny. England was much bigger then, because the sea was lower. Humans were still nomadic. They travelled on foot; a horse was just a good meal for the tribe. People probably lived in groups of less than fifty people, and they hunted animals and fish. They walked and hunted all the way from England to Denmark. Today it's the North Sea, but then it was marsh and low hills full of animals, with rivers full of fish. We call this area Doggerland. It is dark green on the map.

People probably lived in groups of less than fifty people, and they hunted animals and fish. They walked and hunted all the way from England to Denmark. Today it's the North Sea, but then it was marsh and low hills full of animals, with rivers full of fish. We call this area Doggerland. It is dark green on the map.

There was still a problem with the climate. As the days got warmer, ice everywhere on planet Earth was turning into water. Sea levels were rising. Today the forests and marshes of Doggerland are under the North Sea, covered by 15 to 50 metres of water.

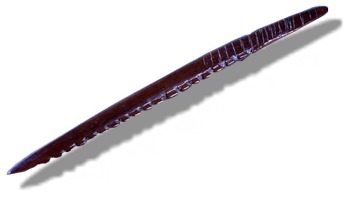

From time to time, a modern fishing boat in the North Sea pulls up a stone tool or a piece of wood or bone carved by the people who lived there, like this harpoon head. Doggerland people had boats too; small boats for rivers and lakes, and perhaps for the beach in nice weather.

From time to time, a modern fishing boat in the North Sea pulls up a stone tool or a piece of wood or bone carved by the people who lived there, like this harpoon head. Doggerland people had boats too; small boats for rivers and lakes, and perhaps for the beach in nice weather.

A digression about boats

The oldest sea boat we have found in Britain was made only 4,000 years ago, but people in Europe must have had good sea boats thousands of years before. About 10,000 years ago people arrived on Cyprus, which has been an island for 5 million year. The people who first went to Malta and to Skara Brae in Orkney about 5,000 years ago also knew how to make good boats, but we don't know what their boats looked like.

The oldest boats were rafts (several trees tied together); dugout canoes (a dugout is a boat made in one piece from one tree); multihulls made of two or more dugouts used together; and skin boats (a skin boat is a big wood basket or frame, covered in leather).

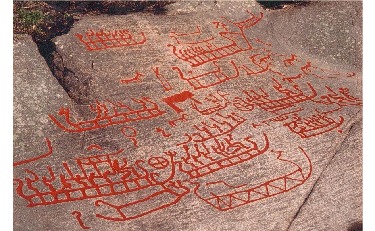

Skin boats were used in Norway in the Bronze Age, as in this rock art from Kalnes.

Skin boats were used in Norway in the Bronze Age, as in this rock art from Kalnes.

Like a basket, skin boats are strong when they are new, because they are light and flexible. When a skin boat is old, it is as delicate as violin. It could survive for thousands of years, but only in a very dry or very cold place.

As a result, the only prehistoric skin boats that archaeologists have found are the umiaq, baidarka and kayak used in the cold dry parts of Alaska and Greenland.

Prehistoric people in the Pacific made good multihulls, and we know there were some very large dugout canoes in Stone Age Britain, but I personally believe that the people of Skara Brae made skin boats. They certainly used a lot of intelligence and creativity to make attractive houses. Skara Brae is a pretty little Neolithic village in the Orkney islands, north of Scotland. Only a maniac would try to travel to Skara Brae from the Scottish mainland by raft or in a small open canoe. The sea here is the Pentland Firth. The water is cold, sea currents are very fast, it is usually windy, and the Pentland Firth is a dangerous place even for modern yachts and ships.

However in a good skin boat you can make a serious journey. An umiak could easily carry an entire family and all their things across the Bering Strait or the Davis Strait. Irish curraghs often transported cows and other heavy loads to Atlantic islands, and one crossed the Atlantic in Tim Severin's famous Brendan Voyage. The photo is of reconstructed Basque skin boat which sailed 800 km along the dangerous north coast of Spain in 2001.

However in a good skin boat you can make a serious journey. An umiak could easily carry an entire family and all their things across the Bering Strait or the Davis Strait. Irish curraghs often transported cows and other heavy loads to Atlantic islands, and one crossed the Atlantic in Tim Severin's famous Brendan Voyage. The photo is of reconstructed Basque skin boat which sailed 800 km along the dangerous north coast of Spain in 2001.

The earliest historian of Britain, Julius Caesar, found that skin boats were used there, and the curragh and coracle are skin boats that are still used in the British Isles today.

European culture, including farming techniques, bronze, iron and language, came to Britain not on foot but by boat.

This is an article about language; I have talked about boats to make two points: That many Stone Age people were extremely intelligent and liked to travel; and that we know very little about their abilities.

6,500 years ago

Planet Earth continued to get warmer and the sea level continued to rise. The land bridge between Britain and the Netherlands disappeared under the sea, as it always did at the end of every ice age for 450,000 years. Click here for a newspaper article with a map.

Planet Earth continued to get warmer and the sea level continued to rise. The land bridge between Britain and the Netherlands disappeared under the sea, as it always did at the end of every ice age for 450,000 years. Click here for a newspaper article with a map.

More time went by, and the climate got even warmer. 6,000 years ago, the weather in England was pretty good, and people started doing a little farming. We call this time the Neolithic, which means the New Stone Age.

At about this time, Neolithic people of the Middle East had at least one clean, comfortable, attractive town with windows, wall painting on walls covered in plaster, pottery, sculpture and sophisticated farming. That was at Çatal Hüyük in Turkey. In the western Mediterranean there were astonishing temple complexes on Malta, including the Hypogeum which looks like something from Ancient Egypt but is hundreds of years older.

Late Stone Age people often rode horses. In Britain, their culture was one of communal effort; hundreds or even thousands of people would work as a group to build ceremonial structures and places such as Stonehenge. In northern Europe there was industrial flint mining at Spiennes in France as well as at places in Denmark, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, Sicily and Krzemionki in Poland. There was industrial salt mining at Hallstatt in Austria. At this time in Britain, there was industrial production of stone axes made with flint from deep mines at Grimes Graves and from greenstone that was mined at Langdale. Hmm. Would you rather be a hunter-gatherer, or work in a mine?

It was a dangerous time too; no law, no police, and farmers needed land, water and slaves. With farming came war. The first farmers in Germany and Austria were part of the Linearbandkeramik (LBK) culture, who seem to have attacked their neighbours quite often, with torture, mutilation and cannibalism. At Schöneck-Kilianstädten, 26 men and children were killed and thrown into a pit. The women were probably taken as slaves. At Talheim, 34 men, women and children were killed. At Schletz-Asparn in Austria, the same happened to at least 67 people. At Herxheim, 450 people were killed and eaten. Many of the victims had been injured in earlier violent incidents but had recovered. Of course, we know about these massacres only because a lot of people were killed and then buried. If the bodies had been left on the ground for animals to eat, there would be nothing to find 6,000 years later. A lot of skeletons from the late Stone Age show that the person was killed with a club, or with an agricultural tool such as an axe or an adze, or with a hunting tool such as a spear or arrow. There was no armour.

4,500 years ago

In Britain, almost the entire population was replaced in just a few hundred years by another group of people who came from Europe with a different culture - that of the Beaker people. Usually, a total change of culture is the result of "decapitation". A small number of invaders with better weapons arrives, they kill the leaders of the old culture, and become the new leaders. However, DNA evidence suggests that the people who first started building at Stonehenge were completely replaced. See Nature, 8 March 2018. Their population had been decreasing for 1,000 years, perhaps because of disease or poor farming practices. They were dying out. The Beaker people seem to have helped with this process.

They're called the Beaker people because of their distinctive drinking cups. They were soon hunting, farming, trading, mining, and producing copper and tin. We don't know whether they played a big role in building the Stonehenge that we know today. Generally, the Beaker people seem to have preferred building smaller earthworks for their villages, not enormous national ceremonial centres. We can think of them as invaders, but skeletons from after the arrival of the Beaker people show much lower levels of violent injury and violent death. The DNA of the Beaker people shows that this was the end of a migration that started long before in the Pontic Steppe (Ukraine and south-west Russia). They almost certainly had priests and poets whose job was to remember. There are no written records from this time, so we can't be sure, but it is likely that they brought Celtic languages (today's Welsh and Gaelic) to Britain.

What was happening in other parts of planet Earth 4,000 years ago? Well, the ancient Chinese were making silk, cities and perfect ceramics. In Sumeria, people were writing literature. The ancient Egyptians were building pyramids and keeping accounts. The Minoans were recording their comfortable and civilised life in wall paintings at Akrotiri on the island of Santorini (Thira).

On the Atlantic coast of Europe, there was more rain and less sunshine than in the Mediterranean, but there was still a lot of activity. All the way from Spain to Britain, Ireland and Denmark, the Atlantic coast had similar weather, plants, trees and fishing, and the people had similar lifestyles and farming.

We don't really know what languages people spoke in Britain 6,000 years ago, or even 4,000 years ago.

We don't really know what languages people spoke in Britain 6,000 years ago, or even 4,000 years ago.

However, experts believe that most modern European languages are based on a Stone Age language from near the Black Sea. This language is now called proto-Indo-European (PIE). It spread out west into Europe and east into India, and as it spread it changed. Language changes all the time. We all know that the Latin word for horse was equus, which gives us English words like equestrian and equitation, so why don't today's Latin languages use similar words? Instead they use cheval, cavalier, cavallo, cavaliere, caballo and caballero. These are from an informal Latin word caballus which meant a cheap horse or a military horse.

The original PIE language changed a lot in 6,000 years. In India it became Sanskrit, in Greece it became Ancient Greek, and in Italy it became Latin. The Celtic and Germanic languages also came from PIE. In fact, every modern European language except Basque, Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian comes from this one ancient language.

We can still see the connections in words like me, is, mother, brother and ten, which are very similar in PIE languages. The English word horse may come from the PIE word kurs-, to run. The English word star has probably changed very little in 6,000 years and 6,000 kilometres:

| Sanskrit | Hittite | Greek | Latin | Italian | Spanish | French |

| star | shittar | aster / astron | stella, stellae | stella | estrella | étoile |

| Saxon | Old German | Norse | Swedish | Dutch | Welsh | Breton |

| sterro | sterro | stjarna | stjärna | ster | seren | sterenn |

Also the English words father, the less formal dad and the technical English words that come from Latin (paternal, patrimony, patronising):

| Sanskrit | Hittite | Greek | Latin | Italian | Spanish | French |

| pitṛ, pitár | attas | patēr | pater, patris | padre | padre | père |

| Saxon | Old German | Norse | Swedish | Dutch | Welsh | Breton |

| fæder | fater | faðir | far | vader | gwaladr, tad | tad |

So much for the common words star and father. Even unusual words often have a very long history. Let's look at beaver (the big brown animal that lives in rivers and cuts down trees). Most Mediterranean languages now use castor, which came from Greek via Latin, but half of Europe still uses a version of the PIE > Sanskrit word bábhru. Today you can hear almost the same word in parts of west-central India and parts of western Scotland, separated by at least 3,000 years:

| Sanskrit | Avestan / Zend | Greek | Latin | Italian | Spanish | French |

| bábhru, babhrús | bawra, bawri | κάστορα (kastor) |

fiber (early Latin), |

castor | castor | bièvre (early French) castor (from 1750/1800) |

| Saxon | German | Norse | Swedish | Dutch | Welsh | Breton |

| bibar | Bibar | bjorr | bäver | bever | afanc | bever, bieuzr (old Breton) avank (later Breton) |

| Czech | Slovak | Slovenian | Polish | Danish | Irish Gaelic | Scottish Gaelic |

| bobr | bobor | bober | bóbr | bæver | bébhar | beabhar |

The Bronze Age : pre-Celtic culture

The Bronze Age started in Iraq about 5,000 years ago, and in Britain about 3,000 years ago.

Bronze is a very useful metal. It's an alloy (a combination) of two other metals, copper and tin. It melts at only 950°C so it is easy to produce. If you want an axe or a sword, bronze is much better than stone. It's stronger, and when you know what you're doing you can make a bronze axe much faster than a stone axe. This new technology made it possible to have holidays, commerce and wealth (rich people).

3,000 years ago

Bronze started a whole new culture of farming, art and trade. In central Europe, the social unit was no longer a small nomadic group. It was a group of hundreds or thousands of people, who lived in permanent villages and small towns surrounded by farms. We call this new social system the Urnfield culture, and it spread quickly across Europe.Of course, humans also use new technology for fighting. A rich man in the Bronze Age could have good metal weapons, bronze and leather armour, and a horse to ride. A rich elite has servants, followers and land. Fighting usually follows. In one Bronze Age battle in the Tollensetal (Tollense Valley) in Germany were there were 100 or perhaps even 200 dead.

In the late Bronze Age, a rich man could have many horses, battle chariots, a hundred servants and a palace to live in. The use of bronze probably did result in the creation of a city of Troy or Ilium in Turkey, and then its destruction by thousands of Bronze Age warriors who arrived in hundreds of ships. This "Trojan War" is the story in the Iliad poem that Homer wrote 400 years later. The more archaeology we do, the more it seems that there was some truth in the story.

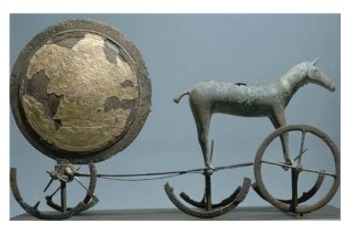

In the Bronze Age, the horse was a central part of European culture, imagination and art. This large bronze sculpture of a horse pulling a chariot was made in Denmark about 3,200 years ago. In the chariot is a bronze disc, covered in gold to look like the sun.

In the Bronze Age, the horse was a central part of European culture, imagination and art. This large bronze sculpture of a horse pulling a chariot was made in Denmark about 3,200 years ago. In the chariot is a bronze disc, covered in gold to look like the sun.

European people had excellent ships, which carried products everywhere in the Mediterranean. They had sophisticated musical instruments such as the lyre, which was like a guitar with 7 strings, and the lur which was a very long trumpet made in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, north Germany and Greece. A lur could be two metres long, made of thin bronze, with a lot of decoration.

In Britain 3,000 years ago you could buy European copper and tin. We know this because a boat carrying ingots of copper and tin sank in the sea near Salcombe in England. There was real international trade. A Bronze Age person in Britain could buy ceramics, bronze tools, axes, swords and mirrors, gold jewellery, amber from the Baltic, and in some places even wine from Greece.

We don't really know what languages British people spoke during the Bronze Age.

The Iron Age : Celtic culture

Bronze is a wonderful metal with very good strength and excellent resistance to corrosion, but it's a little too soft to make good tools and weapons. Also, you can't make bronze without copper and tin, which are not easy to find. There could not be enough bronze for everybody. Iron was different, because in some parts of Europe there were many deposits of iron ore, often close to forests or coal deposits for fuel. Iron is more difficult to make and it rusts when wet, but it makes very sharp and durable tools and swords.

In the Mediterranean area, people first made iron about 5,000 years ago but it was a long time before they really understood the technology. The reason it is more difficult to produce iron than bronze is that iron does not melt until the high temperature of 1,538°C. Serious production of iron and steel started about 2,900 years ago in Jordan and 2,500 years ago in western Europe.

2,500 years ago

As soon as people really understood how to make iron and how to use it, it became much cheaper than bronze. It's a stronger metal, which made it possible to produce much better agricultural equipment like the plough. Better agriculture meant that people could have bigger families and more leisure time. Everybody could have a good knife, a good axe and even armour for war. Suddenly, it wasn't just a few rich people who had good equipment for fighting. Everybody could be a warrior. European culture changed again.The Urnfield culture of the Bronze Age didn't disappear, but it changed into the Hallstatt culture and La Tène culture. Here is the original blade of a La Tène sword:

We often call these cultures Celtic or Keltic. They started in Austria and Switzerland, and expanded. Celtic art and technology went out across Europe. So did Celtic attitudes. In the new culture, fighting was a central part of life. Fighters, traders and musicians took the new cultural ideas to new places, and they also welcomed ideas and products from the Mediterranean. Soon there was a similar culture everywhere in Europe, except for Italy and the forests of the north. Because the Celts liked to fight each other using their iron weapons, a lot of Celtic villages had walls.

Most British people had a very simple life in the Iron Age. We know this from a man called Pytheas who, in 325 BC, decided to go looking for amber. He lived in the Greek colony of Massalia, which is now Marseille in France. The western world at this time was dominated by Greece and Greek trade. Carthage was an important trading city, and so was Rome which now dominated half of Italy, but Greece was far more important. There were Greek colonies all round the Mediterranean, and an empire under Alexander the Great that went all the way from Egypt to India. There were many literate Greeks at this time, able to enjoy 300 years of poetry and stories by Homer, Hesiod, Sappho and Aesop; history by Heredotus and Thucydides;and philosophy by Aristotle and Plato. Pytheas used his literacy to write what he saw of the lands in the north Atlantic.

Amber was an expensive material. People in the Mediterranean bought it from traders who carried it overland from the Baltic. Pytheas knew only that it came from the north, and he wanted to know where. He decided to explore by ship. He sailed up the Atlantic coast of Europe. He didn't find any amber in Britain, but he did find people who lived quiet lives in small houses with roofs made of thatch. The Britons grew wheat, and were famous only for using horses and chariots in war, and for producing tin which they sold to traders who came from Europe on ships.

Celts in different parts of Europe didn't all look the same, and they didn't all speak the same language or have exactly the same religion. We don't know if the individual tribes thought they were part of a European Celtic culture. However they did trade with each other, and Celtic fighters from different tribes sometimes got together to fight non-Celtic people in Greece and Italy.

Western Europe was a Celtic region until the Roman army arrived. Today there is not much sign of Celtic culture or art anywhere in Europe. Some shepherds still count sheep using Celtic numbers (yan, tan, tethera, methera, pip, sethera, lethera, hovera, dovera, dick) and in some parts of Britain you can still hear Celtic languages. These are Welsh and Gaelic. There are still Celtic place-names in England, for example "avon" which means river. In Welsh the word is "afon" and in Irish and Scottish Gaelic it's "abhainn".

About 250,000 people prefer to use Welsh or Gaelic for family conversations. However, like the other 60,000,000 people in Britain they usually prefer English for technical discussions about work, business, law, engineering, medicine, etc.

Welsh - a Celtic language

When the Romans arrived in 43 AD, most people in Britain spoke different dialects of Brythonic. In Wales, Brythonic evolved into Cymraeg or Welsh, and the Cornish also continued to speak a very similar language. Today, Cornish is dead but Welsh is still the favourite language of more than 200,000 people in North Wales and central Wales.

Road signs in Wales are in two languages, for example the city of Swansea in English is Abertawe in Welsh.

Road signs in Wales are in two languages, for example the city of Swansea in English is Abertawe in Welsh.

All languages change, and Welsh is no exception. It has words from Latin (eglwys means church, from the Latin word ecclesiastica; perygl means danger from the Latin word periculum). It also has words from French, and from English including snooker, nuclear and power with the Welsh spellings snwcer, niwclear and bŵer.

Not many modern English words come from Welsh. Apart from some specifically Welsh objects (coracle, cwm, eisteddfod) and some names of places and people we have only corgi, crag and gull.

NOTE about the Breton language: When the Roman army left Britain in 407 AD, the remaining people were two million Britons who still spoke Brythonic languages. Then Angles and Saxons arrived from Denmark and north Germany, bringing Germanic languages and customs. The savage Anglo-Saxon invaders did not get far into Wales or Cornwall but they were difficult and dangerous neighbours, and so were the Irish. Between 450 and 650 a lot of Britons left Wales and Cornwall to find safety across the sea in Armorica. They took their Brythonic languages with them, so the name of their new home changed from Armorica to Bretagne. That's why Great Britain is "great". It's not because we British think we're fantastic. The British lived in Britannia major (Great Britain). Bretons lived in Britannia minor. By 1300 Britannia minor was often called Petite Bretagne or Lasse Brutaine, which mean Lesser Britain. Today it's Breizh to the Bretons, Brittany to the British and Bretagne to the French. The Merovingian kings controlled France but neither they nor the later Carolingian kings could control Brittany. The Breton people were independent for 500 years, until they became subject to France in 942. Brittany finally became part of France in 1547.

Gaelic - a Celtic language

Gaelic is another ancient Celtic language. It is spoken in some parts of Scotland and Ireland. The language is similar in the two countries, but the pronunciation is different and there is also some different vocabulary.

- Irish Gaelic (Gaeilge or just Irish) is still used in the extreme west of Ireland, where in some schools all the lessons are in Irish. Somewhere between 20,000 and 100,000 people in the extreme west prefer speaking Irish to English.

- Scottish Gaelic or Gàidhlig is also used mainly in the extreme west of the country, along the Atlantic coast. Fewer than 60,000 people can speak it. In 2010 fewer than 700 children used it as their main language at home.

Britain joins world history

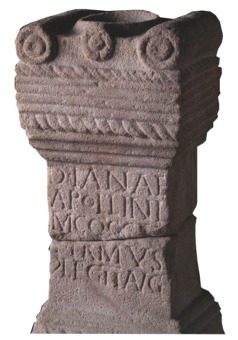

The Roman Empire : Latin

The Roman military machine first came to Britain more than 2,000 years ago, when Julius Caesar invaded in 55 BC. He was interested in the people, and he was the first to write an accurate description of British life.

In the south of England, he found the same tribe (the Belgae) that he had met in France, which was then called Gaul. At that time, Rome was not strong enough to hold Britain and its armies soon left.

1,970 years ago

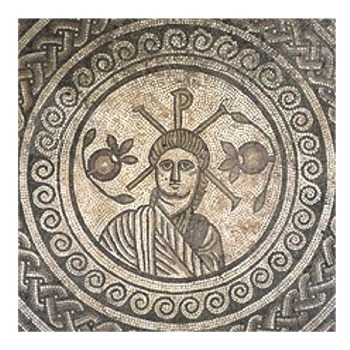

After an absence of nearly a century, the Romans came back in 43 AD. This time they came to stay. Most of Britain was part of the Roman Empire for the next 350 years.The good thing about living in the Empire was the pax Romana, which was peace under Roman control. You had to pay tax, you couldn't have a private army, and maybe you could not have your old religion, but the Roman army protected you from your enemies.

There were good roads and public buildings, and for some people there were houses made of bricks, central heating, medical care, education, a job in an office, and wine to drink in the evening. There was also Christianity, which became an important public religion of the Roman Empire in 313 AD.

There were good roads and public buildings, and for some people there were houses made of bricks, central heating, medical care, education, a job in an office, and wine to drink in the evening. There was also Christianity, which became an important public religion of the Roman Empire in 313 AD.

The men of the Roman army didn't all come from Rome. Most of the Roman soldiers in Britain were from Germany or Spain, but as long as the Empire stayed in Britain, Latin was the official language for administration, law and international trade.

Then in 376 AD a tribe called the Visigoths came from somewhere near the Black Sea and entered the Roman Empire. Rome was not strong enough to defend its entire empire, and in 383 AD Rome had to abandon Scotland and Wales. The last Roman army left England in 407 AD. It never returned. The Visigoths defeated several Roman armies and entered Rome in 410 AD. In Britain, the fall of Rome was followed by the Dark Ages, from which very little history survived.

However, Latin continued to be the language of Christianity in Europe for another 15 centuries. That meant it was the language of education and books. Until about 1750 all intellectuals and doctors used Latin for science and philosophy. Kepler the German astronomer, Newton the English physicist and Linnaeus the Swedish botanist all wrote in Latin, and if they had met they could have spoken to each other in Latin.

Until about 1800, all educated people in Europe learned Latin. When you died, your monument in church was written in Latin. Some English school-children learn it now; I studied it myself at school for two years.

Germanic invaders - old English

Even while Britain was part of the Roman Empire, Germanic people called the Angles, Saxons and Jutes often attacked the east coast. They came from what is now Jutland (Denmark), Friesland (Netherlands) and Schleswig-Holstein, most of which is now in northern Germany. As soon as the Roman army left in 407 AD, thousands of them came to England, and this time they came to stay. They took the best farmland, they had British slaves, and they started families and new communities.

1,600 years ago

When the Romans left, the British tribespeople living in England were soft after 350 years of peaceful, civilised life as part of the Roman Empire. They were farmers and townspeople, not hunters and fighters. Many of them worked in offices, warehouses or factories, many could read and went regularly to Christian churches.The Germanic tribes were fierce. The name "Saxon" comes from the seax, which was a sort of fighting knife or dagger. Some Germanic tribes still collected the heads of their enemies. When a Saxon boy died, even a baby a few months old, he was buried with a sword and spear. The country of England was named after the Angles, and the regions of Wessex, Essex and Sussex were named after the Saxons.

The Saxons made beautiful ships and gold jewellery, and they had trading connections which let them buy things as exotic as elephant ivory from Africa, but these early Germanic invaders did not write down their stories and songs. The high-status person in Anglo-Saxon society wasn't the priest or the rich merchant; he was the warrior with a horse, a sword made of laminated iron and steel, and jewellery of gold, amber and ivory.

The Saxons made beautiful ships and gold jewellery, and they had trading connections which let them buy things as exotic as elephant ivory from Africa, but these early Germanic invaders did not write down their stories and songs. The high-status person in Anglo-Saxon society wasn't the priest or the rich merchant; he was the warrior with a horse, a sword made of laminated iron and steel, and jewellery of gold, amber and ivory.

In 500 AD, Germanic was (more or less) a single language in Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and the eastern side of England. 1,600 years is a long time, and all these languages have changed a lot. I'm English, and I can't understand anything in a German film or book. I can understand a little in Swedish.

Here's some Old English, from the story of Beowulf, a poem that was written in England. It's a long poem about heroes and monsters, but the people and places really existed in Denmark in about 550 AD. The story was probably told in about 650 AD and written down some time in the next three hundred years. During this periods, people from Denmark, Germany, Norway and Sweden often crossed the North Sea to and from England in 30-metre sailing ships.

Hwæt! Wé Gárdena in géardagum þéodcyninga þrym gefrúnon·hú ðá æþelingas ellen fremedon.

Listen! We spear-Danes, in the old days of those clan-kings, heard of their glory and how those nobles did brave things.

Although I'm English and Beowulf is written in Old English, I can understand less than 2% of it. I know that Beowulf is a man's name, and that it's a typical kenning, which was a poet's game with words. Instead of talking about the sea, a Saxon poet would talk about the "whale road", and a battle wasn't a battle, it was "a storm of spears". Beowulf meant "bee-wolf" which was just another way to say "bear", because bears like to eat honey. Of course they could have called him Bjorn, which means bear.

You can still see Old English in modern English, in any word with a "th":

- The Old English letter þ (thorn) was the "th" sound in words like thing, earth and south. An "atheling" was a Saxon prince or noble, so "æþelingas" means "nobles".

- The Old English ð (eth) was the "th" sound in words like this, that and them

My father studied Old English at university, and he may be the last person on the planet who ever spoke it as a living language. When he was about 60 he had a serious road accident with a bad head injury. He woke up in hospital, unable to speak modern English. For nearly a week he could speak only Old English.

The long, technical words in English are usually based on French or Latin but the little words that we use all the time are Germanic. All these words come from Germanic:

to come / came, to find / found, to have / had, love, hate, look, watch, eat, drink, can, could, know, guess, sit, stand, all, most, this, that, them, bread, good, fine, work, blue, green, red, foot, knee, arm, hand, shoulder, finger, ring, day, night, old, young, man, father, mother, brother, sister, daughter, son, cold, snow, frost, rain, water, plough, spade, shovel, garden, house, fish, mouse, milk, wind, winter.

English also has a few longer Germanic words such as bedecked (bedeckt), hinterland and forbidden (verboten), and more German words that arrived recently such as delicatessen, dollar (thaler) and the others listed at the end of this page.

When the Germanic tribes arrived in Britain they were a violent people, but over the next 150 years they calmed down a lot. In about 560 AD the Jutish king Aethelbert ruled the county of Kent in south-east England. He married a French Christian princess, and in 597 AD he welcomed Saint Augustine to Canterbury. Augustine was an Italian monk who came to convert the Jutes and Saxons to Christianity. Aethelbert's wife Bertha and their daughter Ethelburga are both now considered to be saints, and the daughter is buried in the church she founded in 633 AD, in my mother's village of Lyminge.

1,220 years ago

By 790 AD, the Saxons were a peaceful Christian nation producing books of history, poetry and religion. They had built a lot of Christian churches that still exist today.

At that time, however, pirates from Denmark, Norway and Sweden started regular attacks on England and France. These were the Vikings, and they were definitely the new "bad guys". The Vikings spoke another Germanic language called Old Norse. It's similar to modern Icelandic. Some Vikings also decided to live in England, the north of France and other parts of the world including Sicily. There are still a lot of tall, fair Sicilians with blue eyes. In northern England and Scotland, many towns and villages still have Viking names. So do many natural features like hills, valleys and waterfalls. The cities of Dublin and York (Jorvik) were Viking towns. The Vikings also gave us some days of the week (Wednesday, Thursday, Friday) and many of our most common words:

to get / got, to take / took, to want, to die, to seem, anger, bag, berserk, cheap, dale, daze, deer, egg, gale, gang, gap, gift, glitter, haven, Hell, home, husband, ill, knife, law, link, mistake, outlaw, race, root, rune, same, seat, skill, skin, skirt, skull, steak, them, their, they, thrall, thrive, troll, trust, ugly, weak, window, wing, wreck, wrong.

Some of their words, including Viking and saga, did not enter the English language until the 19th century, when Victorian ladies and gentlemen enjoyed reading the Saga of the Earls of Orkney (Orkneyinga saga), the Saga of Burnt Njal (Brennu-Njáls saga) and the Laxdale Saga (Laxdæla saga). No doubt the characters, events and places in these stories are truly 9th century Viking, but all the details like descriptions of clothing are from 13th century Iceland where the stories were first written down. The Viking period officially ended in 1066 with the Norman invasion of Britain. The Viking sagas that we know were not written down until 200 or even 300 years later.

About one-third of words in the modern English language, including most words with the letters "th", come from Germanic peoples including Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Danes, Swedes and Norwegians.

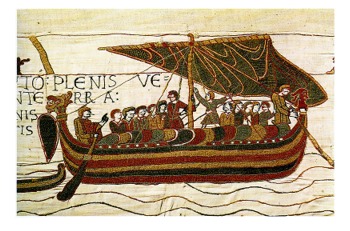

The Norman Conquest : French

On 25 September 1066, King Harold II of England was in the north of England, with his army at Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire. They were fighting a Viking invasion fleet of 15,000 men in 300 ships, sent by King Harald Hardrada of Norway. Although he had fewer men, Harold won the battle. Hardrada was killed and only 24 of the invasion ships ever returned to Norway.

On 25 September 1066, King Harold II of England was in the north of England, with his army at Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire. They were fighting a Viking invasion fleet of 15,000 men in 300 ships, sent by King Harald Hardrada of Norway. Although he had fewer men, Harold won the battle. Hardrada was killed and only 24 of the invasion ships ever returned to Norway.

However on 28 September while Harold was still in York, Duke William of Normandy invaded the south of England. He landed an army of 10,000 men near Hastings. Harold heard the news while marching back to London. 7,000 men of the English army arrived near Hastings on 13 October and there was a battle all day on 14 October. Harold was killed, and William and his friends took the land of the most important Anglo-Saxon lords.

We could see this as a fight between English and French, but perhaps it is more realistic to see both the Battle of Stamford Bridge and the Battle of Hastings as disputes between three groups of Scandinavian invaders. Harold's family had lived in England for two or three generations but they still had Danish names. Harold's brother Tostig went to Norway to give Hardrada the idea of attacking in the north while Harold was in the south waiting for William. William's family were from Denmark or Norway but they had been in Normandy ("land of the North-men") for five generations. During that time, Normandy had become part of France.

French is a Romance language, which means that it is based on Latin, but it also has words from pre-Roman Celtic languages and many Germanic words. The Franks, a group of Germanic tribes from near the Rhine, dominated northern Gaul after the Romans left. Paris was their capital for many years. The name "France" comes from the Franks. The Merovingian kings of France were Frankish, and so were the later Carolingian kings.

Duke William's name was not William at all. He was Guillaume, duc de Normandie to his friends and Guillaume le bâtard to his enemies. He spoke Norman French, which was a dialect of French that included many Old Norse words. His friends also spoke Norman French or other French dialects. He was now King William the First of England but he was still Duke of Normandy, and his lands in France were as important to him as those in England.

950 years ago

In England after 1066 the Normans killed or replaced most of the the Anglo-Saxon lords, nobles and bishops. They created a new ruling class and imported their own culture. For example, Canterbury Cathedral. When the Normans arrived in 1066 they found St Augustine's cathedral, which was built by the Saxons in 597. It was destroyed in 1067 and replaced with a new cathedral, built in a Norman style and using stone from Caen in Normandy.

From William the Conqueror, the kings of England continued to speak some kind of French for 300 years. Richard the Lionheart was king of England from 1189 to 1199. He seldom came to England. He spoke Occitan, Latin and French but none of the "Old English" language of the English working people. The working people were serfs, which was more or less the same as slaves. They had little choice about what work they did, who they worked for, or where they lived.

Here's a sample of Norman French from about this time, from the Song of Roland:

N'i ad castel ki devant lui remaigne; mur ne citét n'i est remés a fraindre, fors Sarraguce, k'est en une muntaigne.

Now no fortress remains in front of him; there are no city walls left for him to take, except for Zaragoza which is on a mountain.

Today's mix of French and English shows how the country was divided under the Norman invaders. English farm workers looked after the living animals and used the Anglo-Saxon words bull, cow, calf, pig, sheep, deer and chicken. Norman lords ate the meat of these animals and called it by the French words beef, veal, pork, bacon, mutton, venison and poultry.

For the Normans, England was a place to live but it was also an excellent business. The words money, accounts, pay, tax, duty and estate all come from old French.

Most of the writing we have from England for hundreds of years after 1066 is in Norman French or Latin, but Old English still existed. Here's a small sample of Old English from about 1100. It's from one of the last Anglo-Saxon Chronicles:

AD 1070 : Her Landfranc se þe wæs abbod an Kadum com to Ængla lande, se efter feawum dagum wearð arcebiscop on Kantwareberig.

I can't really understand these words. I can see they are about Archbishop Lanfranc in England, and I can guess that Kantwarebig is the modern city of Canterbury. Lanfranc was born in Italy. He worked as a teacher in France before he became a monk in Normandy, and finally became the Archbishop of Canterbury. He was an important figure in the Norman administration, and he used his powers to put Norman or French men into all the important parts of the English church. He probably didn't speak much Old English himself.